- Home

- J. Scott Brownlee

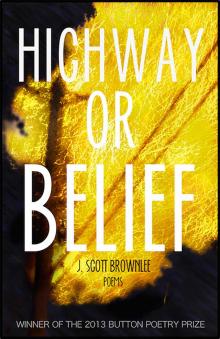

Highway or Belief

Highway or Belief Read online

Highway or Belief

J. Scott Brownlee

Button Poetry / Exploding Pinecone Press

Minneapolis, Minnesota

2014

Copyright © 2014 by J. Scott Brownlee

Published by Button Poetry / Exploding Pinecone Press, Minneapolis, MN 55408

http://buttonpoetry.com

This eBook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. If you do choose to share it with your friends, or if you came across this eBook for free, please note that Button Poetry is a small, artist-run organization, and we rely on your support to continue doing this work. Thanks!

ISBN 978-1-943735-03-7

Praise for Highway or Belief

“What I admire most about the poems of Highway or Belief is how they actively choose to leave no one behind; it is evident that Brownlee has devoted much of his craft to name and resurrect the small town casualties that our country would rather ridicule and forget. This is one of the few books that gets the working class right, and it will ring as gospel for anyone who has attempted to outrun the fractured places that will never leave them.”

—Rachel McKibbens, Final Judge, author of Into the Dark and Emptying Field and Pink Elephant

“J. Scott Brownlee is a Localist, a poet of place. ‘Texan grammar’ enriches the music of his lines. Syllables sputter, sing. An astonishing attentiveness to the people of Llano bleeds through the page. His poems are communal spaces where ‘po-dunk kids’ and soldiers with ‘a new brokenness’ cast tender and brutal shadows. He’s also a chronicler of beauty and the magical. A blue heron alights in one poem. In another he declares, ‘Inside my catfish body, lures bait / two additional fish.’ Tightly crafted and heart-rich, these poems mark the emergence of a poet with a distinctive and important voice. I eagerly await his first full-length collection.”

—Eduardo C. Corral, author of Slow Lightning

for Michael Adams, who believed

Yusef Komunyakaa, who showed me how to build the highway

and Llano’s veterans

Contents

Letter to the Critic Who Questions, Among Other Things, My Poor Use of Grammar

The Last Time I Saw Aron Anderson

English 301

A Body Loves Dismantling

River Metaphysics

Against Allowing Too Much Distance in Place Poetry

Town & Country

Riverbank Elegy

County Lines

Homecoming

Elegy for Soldier Who Returned Without a Voice from the War in Iraq

Bull in the Ring

Sighting Ourselves at the City Dump Site

The Gospel According to Addicts in Llano, Texas

Highway or Belief

Have You Been Washed in the Blood of the Lamb?

Backyard Reckoning

A Conflagration

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Letter to the Critic Who Questions, Among Other Things, My Poor Use of Grammar

This is my pasture. Ride with me. Let’s tour it.

I will teach you enough to re-write your thesis if you ask me

kindly and use Texan grammar—properly requested. Cain’t

we read the poem in a thick dialect? is a valid question.

Cain’t we? Cain’t we? Cain’t we?

(Repetition’s a gift the same way silence is.)

Please explain to me why you took the train arriving years after

settlers first pitched their skin-thin pup tents. I want to

understand your position, though it feels distant now. You

helped the government Comanche chieftains feared—growing

fat on home-front, pillar-pocked and tiled, Romanesque

in its pomp—with its fields collegiate and green, cut

and well-kept. But most discouraging of all? You forgot

about me—assumed speaking in my accent meant “un-

worthy” of New Criticism.

How can he describe anything as beautifully as Shakespeare

with his weed-tumbled, Hill Country voice?

you wondered. And fairly. It’s a thick dialect, after all: full of

shits, ain’ts, goddamns, and Amens. But the true storm grows

here, even so, deep in me. The real story begins like a tree inside

it—tale of this town, I mean—thick mesquite maze of depth

from which voices come, mist-filled

like river echoes on a cool morning skipping rocks,

cut on the wrist blooming red from a barbed catfish

caught in my youth bleeding out, now, ink-like—

language dripping from me just as poetry did the first time

it fell out of the sky, where it rained down freely a week,

once—between clouds and parched earth, wet and dry

perspectives—cattle lowing without provocation

high-pitched, called to congregate there at the center of it

as if Pentecostal: UFO of its glare and sharp gleam

and the beam it shot straight down, each night, into lit-up

pasture—storm-cloud-God-pronounced blue swallowing

ground it touched in the oncoming arc of its fast approaching

—many-mouthed void of it from which voices too humble

to ever have names told me simply,

Be still for once, poet: quiet.

Listening itself finally occurred like a rain of great need

quenching desperation—and then in spite of me. Shit,

I didn’t have anything to say, critic—no clever gloss,

no elaborate reading. There was only blue light, then dark.

The Last Time I Saw Aron Anderson

He played ball like a king, toking hard on cheap blunts

in the batting cage. No one could say shit to him

because he had it grooved to where his swing stayed smooth

even after contact. The same day they named him Aron

his parents left. “They forgot the next a,” he said, smiling

between curves I threw him. “Someday I’m gonna be

All-State. I’ll make my name famous.” People knew about him

for five counties at least. Big scouts showed up to watch

our team play and get whipped by whoever bussed in

from the city to teach us a lesson—that we were piss-

poor, po-dunk kids, ultimately: practice for the bourgeois elite.

But in the district championship, we played a too-wealthy

Wimberley team we defeated barely. And it was sweet,

let me tell you, to stand on that field after it with Aron

saying, “Shit. We did it. We did it.” “Fuckin’ aye,

man. We did”—because he started slinging meth,

and even though he got away and the cops couldn’t keep him

from coming back here, we’ve not spoken since then.

English 301

I can’t tell nobody how we is, babe, but want to shout it.

School ain’t the right place for me. I just sit here and stare

at the whiteboard or whittle some wood out in shop,

where I get A-pluses. I can’t write you’re pregnant

in my English journal because our teacher Miss K’s a Baptist—

so she wouldn’t like that. I came inside you when you asked,

used protection each time before that when I could. . .

when we had it around. Even though you cried “Christ”

then and “Christ” afterward, it was me you prayed to.

I understand the word desire now, I think, mostly

because of you. It’s not something a book could teach me,

&nb

sp; or a show on TV, or a good teacher. . . even Miss K,

who has helped me read some and explained Romeo

when I asked her to: why he and Juliet killed themselves

for no reason. “Aron, the reason was love,” she said.

“That’s a reason.” While I didn’t get what she meant, then,

I do now. Like that gravedigger dude in the last play we read

. . . what was it called?. . . Hamlet. . . I just keep burying

what I don’t want to reach. It’s a goddamn feeling—desire,

I believe—one that’s so powerful I just couldn’t help it

when you said, “Come inside, come inside, come inside.

Make a baby in me.” But now I don’t know what to do,

though Shakespeare makes so much more sense to me:

the scene where everyone dies at the end, what Miss K called

“the tragic climax, the sad part”. . . next to your seat, empty.

A Body Loves Dismantling

& I am not that far away from dis-

integration. Bluebonnets bloom

on thick stalks above me. I cannot

worship them without hesitation—

the kind my heart strains toward

as they do nourishment, which is hard

to find here in my dismemberment.

I put my skull in a polished bull’s now,

& his fits perfectly outside like a helmet

or death-crown made for me by nothing

& no one. Disappearance sculpts it

from clay, calls me Adam, Black Boar

Femur, Bobcat Hip Bone, Coyote Jaw

Lifted Delicately by Wind. Pockmarked

for months until flawlessly polished

by grit churning deep in my gears’

wisdom teeth, I claim multitudes, yes.

You have heard correctly. & I get

a new name with each resurrection.

Dedicate every carrion kill-cry to me.

Let my empty tomb turn to a nest

of catfish: spring-fed, full, forgiving.

River Metaphysics

Inside my catfish body, lures

bait two additional fish—blue &

washed in wet light through the translucent

mesh of my skin scale-netted. This trotline

trinity writes the most crucial poems:

a catfish, a large-mouth, a perch.

Are they three dreams inside

a dream —merely fantastical? No.

They’re experiential—belief wrapped

in muscle: metaphysical flesh I answer to

the way others do God. That’s right:

a perch inside a large-mouth inside

a catfish. Belief gets confusing.

There is the blue river in me & the

black, wider one I can’t explain. In the night

sky it hums like an AC unit set to 58

now. I used to pray directly to it

on my lawn: eyes shut tight

by the vice of my sin

& failure after Baptist meetings.

It had too much to say, & I couldn’t

listen—if not from fear then for the freedom

of the blue future I entered

I had to leave it

in the stars above

me where I knew it belonged— far

from me, darkening—& continue walking.

Against Allowing Too Much Distance in Place Poetry

An elaborate blue heron image

Still holds weight to me—mostly

Because I grew up with them

Nearby, flying. They hatched

At the river, which is not literary

Or canonical. Returning home

From Brooklyn, they teach me

Silence, too, is complicated. So no:

I don’t care if you don’t like them

& have been taught in workshop

Their very existence is sentimental.

I want to take this opportunity

To praise true emotion in poems—

Which is why I’m repeating

The reckless statement

Of my friend from Llano

Who tried junior college

Then cooked ice for a living

Without a trust fund or time

For aesthetics: My name is Aron

Anderson. I get too much pussy

& sometimes over-drink.

Maybe I’m addicted to the worst

Parts of me. Put that in your poem.

Town & Country

Purchase cheap unleaded here

at the cloud-white gas tank

where you meet a no-name

man without fuel money

& a story to tell in exchange

for a lift. “It took two tours

before I contracted the PTS.

Can’t get a lick ’a sleep now.

Got the sense someone’s

after me—hands on my skin

like black widows hatching.”

He pauses, trembling. A red truck

passes him with a bumper sticker

boasting We Voted Bush!

& some tourists in it. “Hey,

you can’t smoke that near

these tanks, boss—you’ll

kill us!” “Hell I will,” he says.

“Back off. I’ll do as I please.

You killed me already.”

Riverbank Elegy

“What will you burn?” the wind asks me.

“I will burn everything, of course,”

I answer it. “And just what do you mean

by ‘everything’?”

“Let me tell you again

to remove doubt fully. I am the arbiter

of flame. I will burn everything.”

“Based on what reasoning?” it presses, curious.

“Think of PTSD after ten years

at war—the frag-mented Iraq in each soldier

from here. I will burn everything because nothing

deserves to be left:

not the town, tourists passing

through it—not, even, the river.

I hope it disappears, soon, drying up.

May its silt bed be split and our war dead

revealed nakedly as a wound

cutting through this county to West Texas

desert. Let their bodies be seen: palely

luminescent. Let us confront

their steel caskets shining—amassed

like so many lures to catch

bass and catfish. Will they feed

five thousand, twenty thousand hungry?

What sum feels great enough? How

are we truly to count and believe—radically

—miracles? I can’t teach you to tell. You want

to know how far, how deep

their hurting goes, what it encompasses?

Walk the bottom of it as they do the river.

Even now, in the dark, though their song

sounds broken, I can hear them singing.”

County Lines

These lines go out to Carlos Castelan,

whom I played trumpet with in marching band.

A mix of white and black, unseemly orange,

and a sort of cowboy hat the whole band wore,

our uniforms were on the whole too memorable.

Carlos was brown, and I was white—

and I was rich, and he was poor—

but we cleaned up the same.

I like to think we both became something

the other one could not: me a writer

in New York City and my friend a soldier

who is still on duty. Picture both of us

laughing if you can, reaching out

with our trumpets on the football field

at night, making music we shared—

marching Fridays our friends fought

new battles in Iraq, a country we had

barely heard of yet. It was

our senior year. We played our fight

song, “Happy Days Are Here Again,”

an ironic tribute to our town’s struggling

team who lost every game because

their coach, a college lineman in the past,

was too conservative to improvise

new plays. He called weak players

faggots on the field. In junior high

he told me, Son, you play like shit,

and I never forgot. By the time

he cut Carlos from the team, both of us

disliked him. The only reason

we showed up was to march at halftime.

We held up signs that spelled Cuck

Foach or just Support the Other Team

until the cops came and arrested us,

reading absurd Miranda rights

with their black tasers pointed

at the centers of our chests. Our bodies

muscular and tense with joy,

we stood up in defiance, then—

protesting what we both believed

—the handcuffs on our wrists

evidence we were brothers.

Homecoming

Upon returning no one noticed

they were back, both inside

Buttery’s, buying tools they needed:

a hammer forged in Taiwan

or Taipei, a sheathed hacksaw

on sale to cut chain off

a hitch or the latch on a gate

that refuses to un-rust

and grant passageway—nails

the color of shrapnel still caught

in one’s lungs—and the other

untouched, even, by a sandstorm

the whole time he toured.

What can never be severed

extends beyond them—

a Kevlar rope invisible

to home-fronters like me,

though I feel its presence

in their body carriage,

which is stiff and relieved

simultaneously—one man

remembered for his valor

and the other one forgotten

not long after it, though

their hearts beat in synch

as if from the same chest

for a speechless instant.

Why were we even there?

the untouched medic asks

the sniper next to him

in the paint aisle. Should I

Highway or Belief

Highway or Belief